Albert Kordiak had a lot to overcome. He grew up in a poor family in Columbia Heights, and he stuttered. Neither circumstance seems to have held him back. Kordiak, who died last month at age 93, was a prime mover and shaker in Anoka County for 32 years. He oversaw the establishment of 14 county parks where there were none previously, started the county library system and created the office of county administrator.

His father, George, emigrated from Czechoslovakia in 1920 soon after the spread of Communism in Europe. He found work in Pennsylvania, where he met a girl of Slovak descent, Anna Yantos. He was 20, she was 14. After a three-day courtship, they married, moved to Minnesota, and established a household near 44th Avenue and 2½ Street, on the edge of Columbia Heights. Albert, their second son, was born there in 1928. He recalled, “There was nothing around there; nothing around there but just wide open prairie or oak trees.”

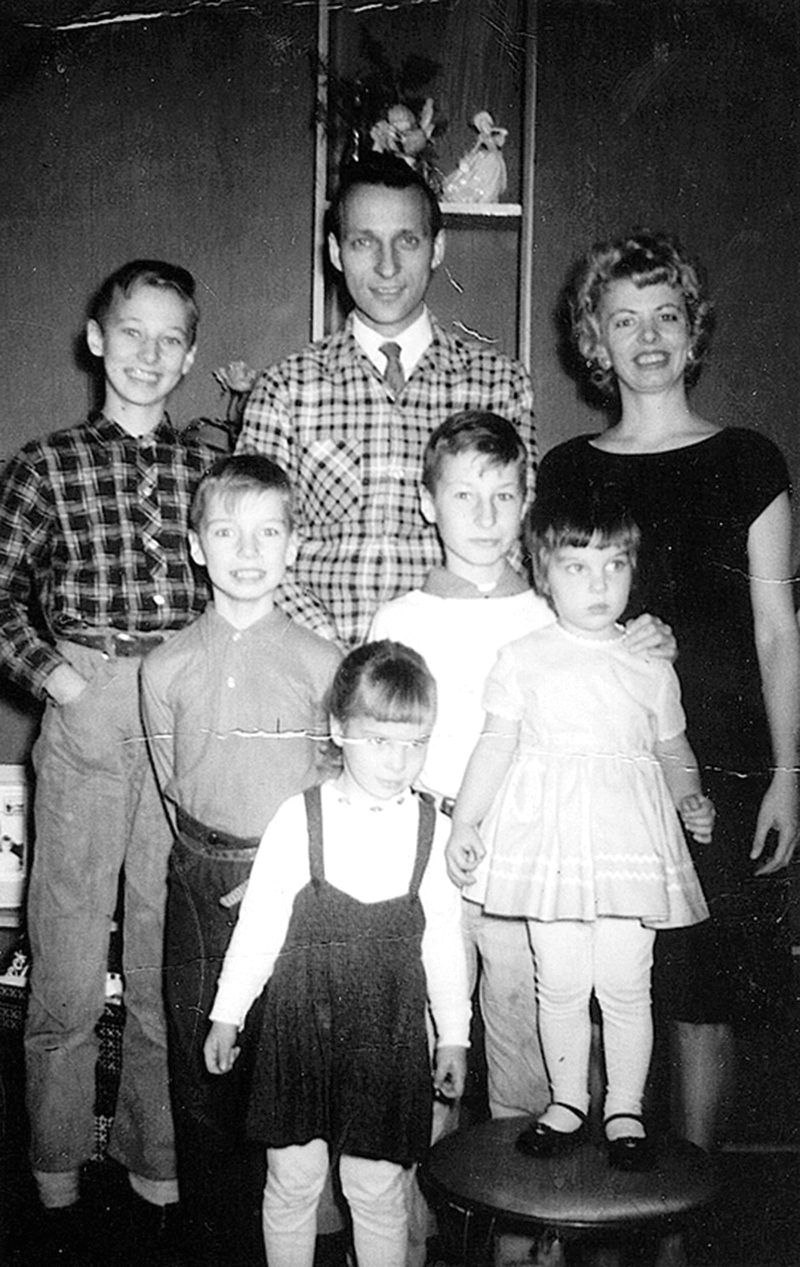

Life was hard. George made a living gathering scrap metal during World War II, though he later worked as a molder in an iron foundry. The house was little more than a shack, cold and drafty. “We all slept in one room upstairs,” Albert told Todd Mahon in a 2009 interview at the Anoka County Historical Society. With seven children (five boys and two girls), Anna economized. “My mother knew how to save every conceivable penny you can save,” he said. “My mother and father went back to Czechoslovakia 13 times.”

Al began working at an early age. During high school, he’d leave at lunch time and work for an hour and a half at Kassler’s Grocery store on 40th and Central, skipping physical education, before returning for afternoon classes. At Albert’s funeral, his son, Jim, said his father had “flunked gym class four years in a row.” Abe Levitt ran the store, and Albert borrowed money from him for books and other school needs. “Abe would write it down, and at the end of the week, he’d figure out who owes who how much. Generally, I owed him more than he owed me,” Al said.

After graduating from Columbia Heights High School, Al went to work at General Electric in the Lumber Exchange Building downtown, where he answered phones. Because of his stutter, he was allowed to answer, “G.E.” instead of “General Electric.” It was there that he met Mildred Wingert, who came from a farm family of 11 near Monticello.

It was a determined courtship. Mildred would catch a ride to go home to visit her folks, but didn’t always have a way back to Minneapolis. Al didn’t have a car, but he persuaded a buddy to drive out west and they “just happened” to stop in Monticello.

Millie saw other guys, which upset Al, who had loaned her an ironing board. He went to her place to get it back, and she told Al she would “rather live a lifetime without an ironing board than a day without you.”

Their honeymoon consisted of a drive around Moore Lake, and they lived in a rented 16 x 16-ft. milk house near Moore Lake where Jim and one of his siblings were born, before the family moved. It had no bathroom, and one light bulb. The family had a toaster, which shared the outlet with the lightbulb. “Life was hard,” Jim said, “and Albert and Millie lived that life.” They were married 73 years.

Al took an early interest in politics. His parents, he said, were “fiercely anti-Communist,” so he joined the anti-Communist movement.

In 1947, he attended a meeting of local Communists at the invitation of a friend. The speaker that evening was the national head of the party, William D. Foster. Al recalled, “I told my buddy, I said, ‘Norris, pretend like you don’t know me ’cuz I don’t want to embarrass you.’ I says, ‘You dirty, rotten, filthy Communist. How dare you preach that filthy Communist filth and garbage standing before our great American flag?’ And then I made the mistake in adding onto it, ‘Long live Franco [Francisco Franco, who overthrew the Spanish government], long live Péron [Juan Péron, president of Argentina].’

“The whole thing took a minute, but then they had me up off my feet and head first I was going out the hall, and they took me out into the hallway, and they beat the hell out of me. . . And rolled me down the steps, and I don’t know why the cops came in just about then, but there were two policemen came in. And they said, ‘Who did it?’ and I said, ‘Those two guys right there.’ Well, it turned out that one of them was Samuel K. Davis, and he was, at that time, the candidate on the Communist ticket for governor of Minnesota. And the other guy was Lionel Bergman. He ran the Communist Daily Worker newspaper.”

Al ended up working with the FBI as an informant, going to the Socialist Workers Party headquarters on the second floor of the Army-Navy Surplus Store on 4th and Hennepin and pretending to read. “I would just close my book and follow somebody down the steps and take down his license number, and when I got a few of them, I’d give them to the FBI.” He testified before the House on Un-American Activities Committee in 1951. Jim was born while he was in Washington, DC.

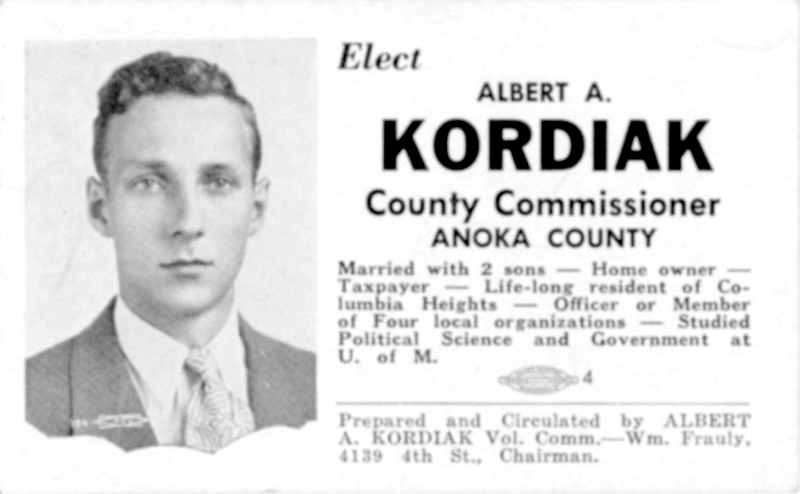

Back home, Al decided to get into the local political scene. He ran for the Minnesota House in 1953 and lost. He noticed that he had quite a bit of support in the southern part of Anoka County, so the following year he ran for county commissioner against Alvin Ittner, who lived behind Kassler’s Grocery. Many people thought Kordiak was too young, but he prevailed – and was re-elected unopposed eight times.

He was working in the service department at Electric Machinery on 8th and Central at the time, and received permission to attend county board meetings during the day if he made his 40-hour work week. He often worked nights to catch up.

The role of county commissioner seemed to be tailor-made for Al. He became a man known for listening to his constituents and getting things done. He saw the burgeoning Anoka County population (35,000 and three cities; today there are 21 municipalities) and foresaw the need for green space.

He brought the matter up at a county board meeting in 1960. “Last Sunday, we took the kids over into Ramsey county [sic]… Lake Johanna, Island Lake, they’ve got a wonderful park system over there. But that’s where we have to go for a good recreation area. Up north and northeast the people have nothing.”

He began lobbying the Minnesota Legislature to allow counties to use condemnation as a tool to purchase land to create parks. The first was a 29-acre parcel on 49th Avenue in Columbia Heights, the first county park in Minnesota. It was later named for him. Together with David Torkildson, Al Kordiak was responsible for creating 14 parks in Anoka County totaling 11,500 acres. “Those parks were the centerpiece of his career,” said son Jim.

The parks became popular with residents and non-residents alike. One group, however, was not welcome. In 1964, the Star Tribune reported, “18 gypsy families camped four days at the north end of the fairgrounds in Anoka and left the area littered.” Sheriff’s deputies asked the group to leave and they complied. Kordiak initiated a ban on overnight parking. Referring to the gypsies, he said, “They seem to be an annual problem for us. I think it is safe to say no gypsy band is going to get approval from any member of the board to set up camp.”

During Al’s tenure, the Anoka County library system came into being and the first county administrator position in the state was created. The Anoka County courthouse was built. He served on the first board of the Metropolitan Mosquito Control District. Kordiak also created a county emergency response system – well before 911 came into being. He was a passionate advocate for counties, preferring the work of pollution control, for example, to be carried out by coalitions of counties rather than the state.

Despite holding down two jobs, he also ran his own income tax business in downtown Columbia Heights. The door was always open to his constituents. One was Mickey Rooney, whose son had acute lymphatic leukemia. “It was almost a death sentence back then,” Rooney said. “I was soliciting ads for the Knights of Columbus newspaper and I didn’t have any health insurance. He got me connected to Blue Cross/Blue Shield.”

The two knew each other socially through the Knights and Immaculate Conception Church. On Fridays, they’d gather at the “Highland Friday Afternoon Round Table (HLFAR),” at the Shorewood in Fridley, Rooney recalled. Regulars included Jim Nicklow, Judge Joseph Wargo, Bruce Nawrocki and Torkildson. The group later moved to Sarna’s. “He was my best buddy,” Rooney said.

Throughout his career, Kordiak focused on constituent service, Jim said. “They just knew him. They liked him and loved him.”

After a lifetime of work, Al decided to step down in 1986. “I worked since I was eight years old,” he told the interviewer at the historical society. “I worked constantly. I was getting tired about that time, and … Jim was getting old enough to run. If Jim hadn’t agreed to run, I probably would have run again.”

Sources

“Acquire Park Sites Before It’s Too Late, Official Urges,” Star Tribune, June 30, 1960

“Anoka County Board Votes Camping Ban,” Star Tribune, July 14, 1964

Interview with Albert A. Kordiak by Todd Mahon, Anoka County Historical Society, Dec. 7 and 14, 2009

Notes from Albert Kordiak’s eulogy by Jim Kordiak

Below: Al Kordiak as a young man. Below, his campaign card. Al and Millie Kordiak and their five children in Columbia Heights. (All photos courtesy Kordiak family)