Lots on the 19 acres of land on the northern border of Minneapolis were platted in 1884, but nobody wanted them.

With tall hills intermixed with swamps, they were a builder’s nightmare. Only a few homes sat atop the hills, and they were run-down and seedy. Some of the properties were tax-delinquent.

In the late 1940s, the City of Minneapolis decided to do something about this derelict portion of the Waite Park neighborhood. It would be more than a decade before urban renewal swept through downtown’s Gateway district, but the term was already on the lips of city council members.

The impetus, naturally, was tax revenue. With very little housing on the land, the city was losing money. During the 64 years the land sat vacant, the city estimated it had lost $500,000 in taxes.

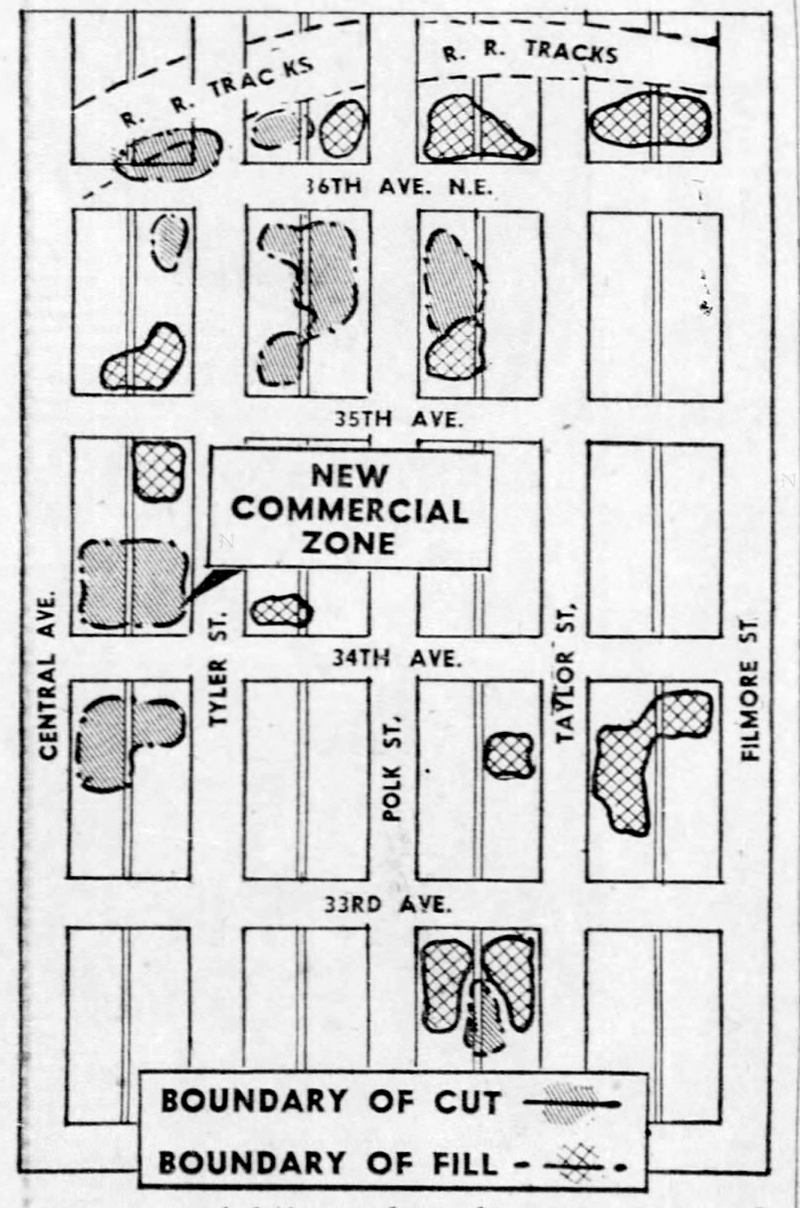

The city council decided to develop the land. They named it the Hi-Lo development because of the topography. The south half of the development was bounded by 34th and 35th Avenues from Central Avenue to Tyler Street. The north half was bounded by Polk Street, Tyler Street, 35th and 36th Avenues, next to what was then the Soo Line Railroad tracks. To make the land attractive to builders, the city decided to re-plat the land and do some extensive landscaping.

The Minneapolis Star was enthusiastic. In a Dec. 19, 1949, editorial, they wrote, “Making the present unsightly and useless swamps and hills suitable for private construction would increase the Minneapolis tax base, improve the appearance of the whole district … The council should be prepared to give quick approval when the project next comes before it.”

Flatter land, bigger lots

The 1884 plats had allowed for 40-foot residential lots and commercial lots 25 feet wide. The new plats called for 55-foot lots to accommodate 43 single houses and 27 duplexes for a total of 97 family units. A half-block shopping center was suggested for Central Avenue between 34th and 35th. When the soil settled, an additional 22 homes were planned for 35th and 36th between Polk and Tyler.

Locally financed and locally administered, the project was the first redevelopment unit to be carried into the construction stage in Minnesota, if not in the entire country, according to Talbot Jones, the project planner. He was the son of Robert Jones, architecture professor at the University of Minnesota and a member of the city planning commission since 1945. Talbot Jones was hired at a salary of $6,000 per year (about $78,000 today).

Unlike today, the Minneapolis City Council was focused on single family homes, not density. The project hit a snag late in 1949 when the committee adopted a motion of Alderman (Council Member) John R. O’Keefe to reject the Hi-Lo plan “because we have not been furnished with sufficient information to decide if it conforms to the development of the area as a whole.”

After further study, building specifications were set. The number of buildings was reset to 62 single family homes and 27 duplexes. Single family homes were to contain at least 1,000 square feet of floor space and duplexes, 850 per unit. Instead of selling multiple lots to developers, the city council decided to sell them to private individuals.

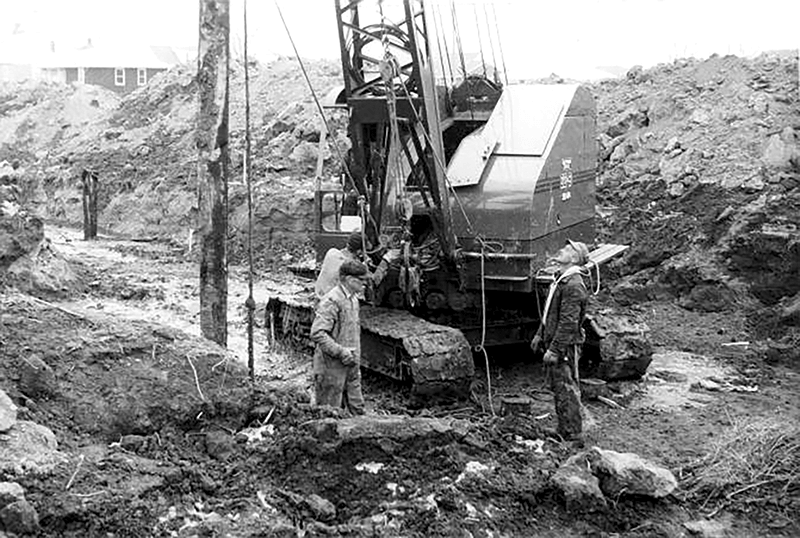

In August of 1950, bids were opened, and Joseph F. Phillippi Dirt Moving Co. was chosen shave off the tops of hills and fill in swamps. The work was expected to take 60 days, and cost the city approximately $45,000.

Digging commenced Sept. 2, 1950. For weeks, tractors, excavators and other earth-hauling equipment crawled over the land, leveling hills and dumping load after load of dirt into the 11 “useless swamps” that pockmarked the area. In all, they rearranged more than 90,000 cubic yards of dirt.

Lots for sale

By the following summer, the lots were ready for building. On July 2, the Minneapolis Tribune announced that 75 parcels, priced at $600 to $1,600 each, were available. Prospective buyers had to submit sealed bids, and housing had to be built on the lots. “The lots being offered are in the vicinity of Thirty-seventh and Central avenues NE,” the paper reported. “They vary in size from 54 x 125 feet to 96 x 140 feet.”

The Tribune also reported that the acquisition and subsequent reconfiguration of the land had cost the city $85,000. The sale value was set at $95,000.

By 1954, Charles Bailey reported in the Tribune, “Total costs of the project so far have come to $98,000. Income from resale of the land has been $57,000, with about $18,000 worth of land still to be sold. This will mean a net cost to the city of about $23,000.”

He noted that property taxes were already offsetting the city’s costs. “Before the project, the land was all but unused, producing almost nothing in taxes. Taxes this year on the 60 homes already built on the 95 lots sold for homes will be over $13,000.”

By April of ‘54, the project was deemed a success. All but 18 lots had been sold and homes built. Original estimates had pegged redevelopment costs at $96,650. “Actually, they ran to $97,794.44,” wrote the Tribune’s William Brooks, Jr. “On the credit side, it originally was figured the land would be resold for $56,050. Instead, the land sold so far has brought in $53,491.80 … The area is now bringing in $25,000 a year more taxes.”

Built without federal funding, Hi-Lo paid for itself within a year (city planners had projected a three-year return on investment).

Brooks calculated that the expected 40-year life of the houses would bring in $500,000 in taxes. The houses in Hi-Lo are 70 years old, still standing and still producing tax revenue.

Could Hi-Lo be built today? Maybe, but times have changed. During the time Minneapolis condemned the land and renovated it, the Minnesota Legislature passed a law stating that cities could only redevelop “depressed” areas where buildings already existed. And then there’s the environmental aspect: Those 11 “useless” swamps would probably be considered valuable wetlands today.

Sources

Kleeman, Richard P., “Housing Group Hires Planner,” Minneapolis Tribune, Dec. 7, 1949

“Hi-Lo Redevelopment Can Help Minneapolis,” Minneapolis Star, Dec. 19, 1949

“90,000 Yards of Dirt Moving in Hi-Lo Project,” Minneapolis Star, Sept. 2, 1950

“Hi-Lo Property Sale Extended for 3 Weeks,” Minneapolis Tribune, July 2, 1951

“Land for Sale in Hi-Lo Area,” Minneapolis Star, July 17, 1951

Bailey, Charles W., “Planners Racing Time to Clear City’s Slums,” Minneapolis Tribune, Feb. 7, 1954

Brooks, Jr., William, “City Housing Project Pays Off,” Minneapolis Tribune, April 11, 1954

Construction workers and some of the 90,000 cubic yards of dirt they moved to “even out” the Hi-Lo neighborhood. (Hennepin County Library)

1949 Minneapolis Star map showing places in Hi-Lo to be graded or filled in. (Minneapolis Star)

“Lots for Sale” sign outside the Hi-Lo development area. (Hennepin County Library)

34th & Fillmore before. (Hennepin County Library)

34th & Fillmore after the Hi-Lo project. (Hennepin County Library)