When settlers from French Canada moved south to Minneapolis in the 1870s, they brought their culinary traditions with them. One of them, a double-crusted meat pie, has kept Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church in good repair for decades.

The pie the Québécois brought with them was a tourtière. Large and very meaty, it occupied a prominent place on the table on Christmas Eve, during a post-midnight mass celebration called réveillon. According to Foodnetwork.ca, “Tourtière was always on the table, and in 17-century Québec, the pie was traditionally served in a cast-iron cauldron and stuffed with cubed meats, often wild game (rabbit, pheasant, or moose).” In 21st-century Northeast Minneapolis, ground pork is the meat of choice.

Parishioners of the church on what was once known as Prince Street probably brought the pies to the church for funeral luncheons, said Debra Hamilton, who heads up Lourdes’ pie-baking operation. The big pies with a flaky crust and savory filling fed a lot of people and would have provided the ultimate in comfort food.

In the 1940s, church women decided to hold dinners that featured the iconic pies. Rachel Gaudette, who lived on 5th and University NE, came up with the dinner idea. “Some of the women blame me for all this work,” she told a Minneapolis Star reporter in 1963. At the time, she had attended Our Lady of Lourdes for more than 70 years and sung in its choir for 50 of those years.

The dinners became a twice-a-year tradition. The menu included tourtières, beets and apple juice. It may also have included au gratin potatoes, a vegetable, French bread, coleslaw and ice cream. In a 2003 article in The Catholic Spirit, Michael Rainville, not yet the Third Ward Council Member, recalled, “The piece of meat pie I had last month tasted exactly the same as a piece I had 40 years ago.”

That consistency is not by accident. In the hands of different bakers, not all pies are created equal, even when you hand them the same recipe. Church administrator Mary Asp recalls hearing stories of arguments over whose pie was the best. Evelyn Lund, who lived on 18th and Jackson, was credited with coming up with the recipe that’s used today.

“We have the recipes for the pies down to a science, mostly because we had to devise a recipe so the amount of ingredients would fit in the kettles we had on hand,” said Lund in 1963. Back then, the bakers started out with 18 lbs. of ground pork. Pies sold for $2.50 each.

The recipe and the process have become more “scientific” through the years, Hamilton said. All the ingredients are weighed. “We try to get 27 pies out of 40 lbs. of meat,” she explained. They’ve tested different brands of flour to see which makes the best crust and made their measurements more precise. Instead of relying on a “cake pan of flour,” they measured the amount the pan held and weighed it so they now have a more precise formula for future pie bakers to follow.

The women instituted an assembly line operation early on. “For instance,” Hamilton said, “one group mixes the ingredients for the pie crusts, which are all handmade and are individually packaged for each pie. Five or six people make the flour, lard and water mixture and form it into balls.” The crust can’t be too sticky, or too dry. The more it’s worked, the tougher it becomes. “If you don’t have a good crust, you don’t have a good pie,” Hamilton said.

After the dough balls are fashioned, they’re passed along to another group, which prepares the dough for a rolling machine that flattens the crust into a circle that’s placed inside a pie tin.

Prior to all this mixing and shaping, a team of four men gather in the church kitchen at 6:30 a.m. to begin cooking the filling, which includes 100% ground pork, onions, a modest amount of bread crumbs — two cups for every 48 pies — to hold the filling together and a secret blend of spices, which the folks at Our Lady of Lourdes decline to name. The mixture is allowed to cool and drain before it’s placed inside the crust. The old recipes called for potatoes, but the bakers found they made the pies too moist to hold up for freezing.

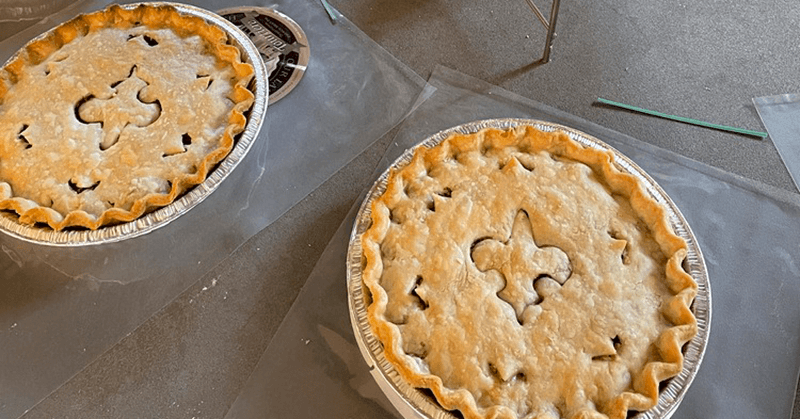

After placing a precise amount of filling — 1.4 lbs. — into the crust, the pie is handed off to Hamilton’s husband, Fred Schilling, a former dentist who’s been entrusted with crimping the delicate top crust. He was taught by Evelyn Lund, who passed along her tourtière-making knowledge before her death in 2002. He cuts vents in the crust to let out the steam and places a fleur-de-lis imprint on the crust, then it’s off to the oven for parbaking.

After a short spell in the oven, the pies are brought to the church’s Hofstede Hall, where they’re allowed to cool, bagged with cooking instructions and taken to the church’s walk-in super freezer, installed in 1989.

Years ago, the bakers used reusable pie tins. On “pie-flipping day,” some of the women would gather to turn the cooled pies out of the pans for reuse. You had to have some dexterity to flip the pie without breaking the crust. That step in the process went by the wayside when the bakers turned to disposable aluminum pie tins.

During a recent neighborhood tour, Rainville, a fifth-generation member of the church, said pie-baking was a way to keep the French Canadian tradition going. Bakers have persevered through the years, even showing up to make filling and roll dough during a blizzard. Pie-baking continued during the COVID-19 pandemic, though at a much lower rate, and with masking and other safety protocols.

Over the course of a year, the parishioners at Our Lady of Lourdes will make 800 to 850 meat pies. Most people buy them for the Christmas and New Year’s holidays.

And then there are the tourists. The church is on the National Register of Historic Places, noted Asp, and is a stop on some city tours. “When I first came here eight years ago, we only sold pies seasonally,” she said. “We had people from Canada stopping here and wanting to buy pies in the summer. Some wanted to take ten or 12 of them.”

She recalled receiving a phone call from a man in Florida who said he’d make it “worth your while” to ship a pie to him. She replied, “But it wouldn’t be worth yours.” Shipping costs would have amounted to more than $600, with no guarantee that the pie would arrive in edible condition.

Tourtières will go on sale at Our Lady of Lourdes, One Lourdes Place, Oct. 31, 8:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m., Tuesday-Friday. Pies are $25 each. If you buy two for $50, you get an an insulated bag to carry them home. Proceeds go toward the church’s historic renovation. Sales will continue throughout the holiday season until the supply runs out.

Lourdes bakers with pies in the 1950s. (Provided)

The Fleur-De-Lis design showcased on each pie.