Some Sullivan Drive residents first thought the canine that was frequenting the path and yards bordering on Sullivan Lake Park in Columbia Heights this spring was a wolf, since they started seeing it regularly around the time wolves escaped from the Wildlife Science Center in Chisago County, said homeowner Barbara Babekuhl.

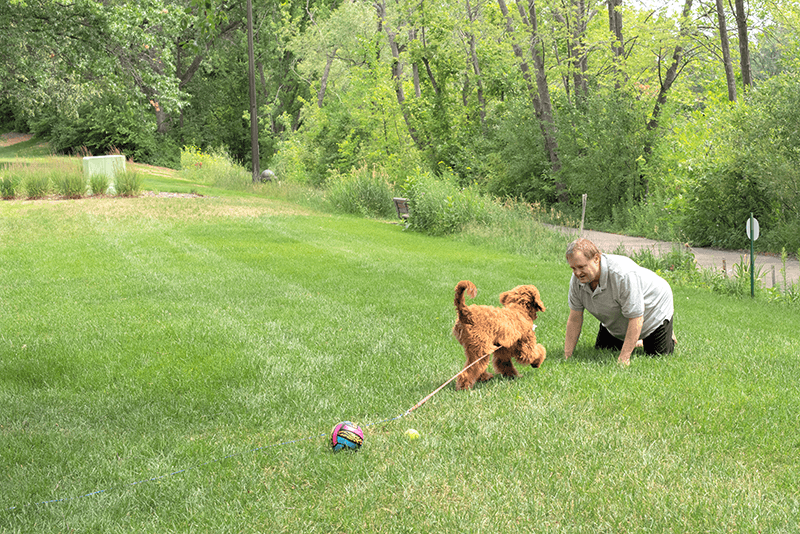

Babekuhl said she figured out it likely was a coyote, not a wolf, and judging from its behavior, she thought that it probably had a den in the grove of trees in a corner of their complex of townhouses. She and neighbors would see the animal on the path as early in the evening as 9 p.m., when people were still out walking, and often at night, when she and husband Dave Scouton were sometimes alerted by the pacing of their miniature Goldendoodle, Porkchop, who would catch the coyote’s scent through the screen on their upper-level porch.

In late May, as a young puppy, Porkchop needed to be let out just about every hour. Scouton was often a little wary, keeping an eye out for the coyote, which, he said moved very fast, “like a magician.” He said he didn’t have “any reservations” about the animal until the night the coyote came bounding toward him and Porkchop, who was and always is on a lead. Scouton dragged the then-oblivious pup into the house, and when he came back out to scare the coyote, the “magician” had disappeared.

Coyote encounters

“Hazing” an animal that approaches or stands its ground in the presence of humans is the right thing to do, says Scott Noland, Forest Lake area wildlife manager with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR). You don’t need an air horn or a water sprinkler, he says, although those certainly can help. He recommends “just being loud and tall,” and to not run away, because the running away triggers the predator-prey response. “Keep eye contact, make yourself big, yell, and back away slowly.” It’s the same thing that you should do with an off-leash domestic dog that’s following or threatening you, he said.

Although some people unnerved by the presence of a wild animal might be eager to have it removed, Noland said trapping and removal can backfire with coyotes. If it’s one that travels in a pack, removing an alpha animal — the leaders and the only ones that will mate — can result in increased fecundity among the remaining coyotes. Other individuals will “backfill” a void left by the missing predator, according to the website of the Urban Coyote Research Project, a long-term study in the Chicago area by Ohio State researchers.

Although it can be disconcerting to have a wild animal coming toward you, what might seem like “charging” might be simply “escorting” intruders from the den. Nick McCann, a postdoctoral associate who manages the Twin Cities Coyote and Fox Project at the University of Minnesota, said coyotes are more territorial when they’re protecting a den and kits, usually between May and July. They also might actually be focused on hunting or another need, pointed out Noland, citing a photographer’s experience with a fox that seemed to be coming right at her, but it was simply seeking, on a hot morning, to lie down in the only nearby shade a few feet away from her.

That said, there is no question that coyotes can kill and hurt pets, said Noland, particularly ones that are unattended or off-leash. Free-ranging domestic dogs might discover coyote dens, then get bitten on the legs — “nips” Noland calls them — as the coyote defends its territory. “It’s a way of just saying, ‘This is my space. You’re too close. Get out of here,’” Noland said.

McCann said coyotes in the metro area are typically between 25 and 35 pounds, the size of a beagle. They stand taller, though, and can seem intimidating, especially in their winter coat. Unattended dogs that are smaller than the coyote can be seen as prey; faced with a larger dog, a coyote will stand its ground and defend its den. “The coyotes size up what they can do and make a decision accordingly,” he said. Having a human presence in a yard, or attached to its leash makes a dog less vulnerable, Noland said.

How frequent are attacks on pets? Noland says the DNR receives five to 10 reports each year from the metro area. Not all are lethal but might require veterinary care. Of course, not all are reported to the DNR, with municipalities likely receiving most of the calls. The City of Bloomington, which has substantial areas of wildlife habitat along the Minnesota River, has kept track of coyote sightings and interactions and mapped them on their web site. That data shows that there were more than 383 sightings from 2016-2021, with three dogs killed in 2016; one in 2017; two in both 2018 and 2019, and none in 2020 nor 2021.

As far as attacks on humans are concerned, Noland said he was not aware of any in the state of Minnesota; the Urban Coyote Project web site says that there have been none in Illinois either and also reports on a more extensive study. The project used media reports and DNR sources to look at the prevalence of coyotes attacks on humans in the U.S. and Canada. In the 21 years between 1985 and 2004 they found 142 attack incidents, with almost half occurring in California and the second largest percentage in Arizona.

In addition to putting pets on leash, not leaving them unattended in yards and keeping cats indoors, Noland said we can reduce likely coyote encounters by not keeping pet food or water outside, and of course, by not feeding coyotes and other wild animals. Bird feeders can attract coyotes because they attract rodents, which are one of the main sources of a coyote’s diet. Cleaning up below bird feeders and fruit trees makes the yard less attractive to coyotes, as does keeping vegetation trimmed, since they are ambush predators. To keep a coyote out of a yard, you would need a fence of at least six feet, with a roll bar on the top, Noland said.

Barbara Babekuhl and Dave Scouton said that they and their neighbors joked about being glad that Porkchop didn’t become a pork chop and also were amazed that a free-ranging little white dog with a limp that lives nearby has so far survived the coyote’s presence.

After the coyote headed toward Scouton and Porkchop, Babekuhl reported it to the police; she said that other residents had also filed reports. They came out and investigated but said they would not do anything unless the animal was aggressive or threatening. Captain Matt Markham of the Columbia Heights Police Department explained in a phone conversation that is standard procedure. Community service officers respond to wild animal complaints but will not do anything unless the animal is clearly acting aggressively toward humans. “They have always been here, hunting at night and disappearing into wooded areas during the day,” he said, speaking of coyotes and foxes. There was one incident in the city in recent years in which a rabid fox needed to be shot; if there was a situation in which an animal needed to be trapped, he said he would likely consult with the DNR.

Noland encouraged people who might be wary about living with a coyote as a neighbor to think about the positive role coyotes play in the urban ecosystem. They are apex predators that keep in check other populations such as squirrels, rabbits and geese, which are often considered nuisance species.

That aligns with Sullivan Drive resident Betsy Command’s response when asked on the path along the lake if she had seen the coyote recently. “It’s moved on,” she said. What made her so sure of that? “Look at all the rabbits.”

SIDEBAR INFORMATION:

Facts about urban coyotes

Sources: MN DNR fact sheet, Urban Coyote Research Project website.

Average weight: 25-35 pounds

Coloration: grayish brown, but can vary from silver-gray to black, with black tip on tail. Yellow eyes.

Habitat: Prefer open areas, such as prairie and desert, but in urban areas, prefer wooded patches and shrubbery that provide shelter to hide from people.

Diet: from scat analysis most common food items are small rodents (42%), fruit (23%), deer (22%) and rabbit (18%) (do not add up to 100% because scat often contain more than one type of food.)

Social structure: Some live in packs consisting of an alpha male and alpha female and closely related individuals. The pack will defend their territories from other coyotes. Some are solitary and travel over large areas, traveling between and through resident coyote territories.

Breeding: Coyotes begin to breed at 2 years old. May pair for life. The alpha pair in a pack mate in February, and others in the pack will help raise the young. In April the female will find a den which can be an existing cavity or dug by the female. Pups are born in April and stay in the den for about six weeks. The number in a litter can depend on food abundance and population density, but generally ranges between 3 and 7 pups.

Coyote Research

Twin Cities Coyote and Fox Project (tccfp.umn.edu/)

For two years, researchers in the University of Minnesota’s Department of Fisheries, Wildlife & Conservation Biology have been investigating observations of foxes and coyotes, then trapping, collaring and tracking their movements via GPS. Through the tracking and analyzing fur and scat samples they hope to learn about the diseases the canids carry, what they’re eating, how they’re using the landscape, and how urbanization affects those factors. Sightings can be reported on the iNaturalist app and also on the TCCFP Facebook page.

The project is funded by the Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund, and partners include the Fish and Wildlife Service, Three Rivers Park District, Friends of the Mississippi, and local municipalities.

Urban Coyote Research Project (urbancoyoteresearch.com)

An ongoing study, started in 2000, of coyote ecology in the Chicago metropolitan area, conducted by Ohio State University researchers and Cook County agencies with funding from Max McGraw Wildlife Foundation. The project’s website has extensive information about coyotes and coyote management strategies, as well as scientific research reports and resources.

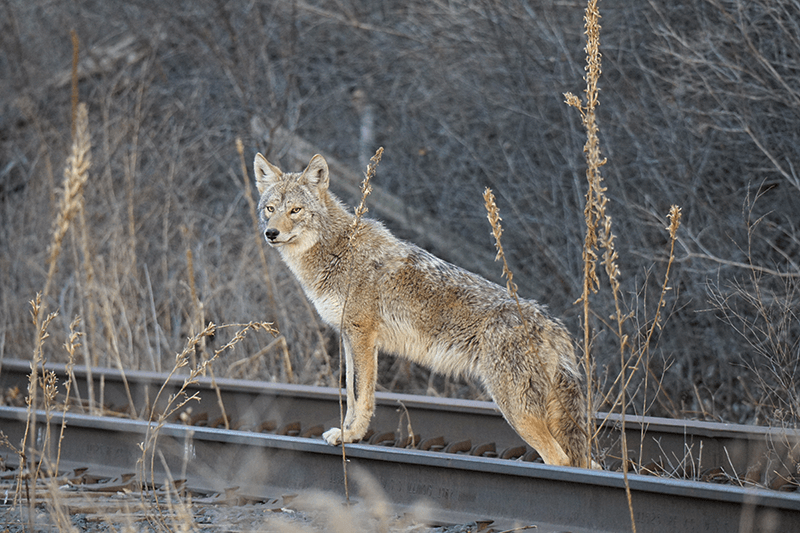

Below: Coyotes often travel along rail lines. (Photo by Tim Regan) Porkchop and Dave Scouton play in their Columbia Heighs backyard, where they previously encountered a coyote. (Photo by Karen Kraco)